|

Livelihood of the People And Home Crafts. Agriculture was and still is the mainstay of the people of the parish and mixed farming has been the traditional method of carrying on that farming. The farms were small very few exceeding 40 acres of arable land with perhaps in some cases, a number of acres of very rough grazing land fit only to support a small number of strong cattle or mountain sheep. However the people were most industrious, skilled in their work and thrifty in their ways so that they were able to support large families, feed and clothe them well so that any visitors to the parish – school inspectors and the like, always remarked on the neatness and healthy appearance of the children. It goes without saying that all this meant hard work for parents from early morning until almost darkness fell, six days of the week, with very little time for leisure. Up to the 20th century the terrible back breaker for the tenant farmer was to put the money together to pay the exorbitant rack rents demanded by the landlords and their agents. Those agents were cruel and ruthless and gave no mercy to anyone. One of the most infamous of those agents was one named Sam Hussey who lived where Edenburn Hospital now stands. He was fired severals times by the Moonlighters but seemed to have a charmed life as he lived to be an old man.

He told a story against himself – a priest on denouncing drink from the pulpit declared that drink had ruined homes, made them beat their wives, starve their children, made them fire at agents and worse than all made them miss them. |

The Parish, regarding the quality of the land may be divided into two parts:

- The land along the valley of the Laune, from Laune Bridge to Gortnascarry with a breath of about two miles.

- The land along the foothills of the McGillycuddy Reeks.

The Laune Valley is very fertile, perhaps as good as any place in Ireland. It has a marl soil with a carbonate of lime content of between 5%. The soil is rich, parts of it contain good supplies of limestone and is suitable for the growth of any kind of crop, wheat, barley, or beet and has fine grass lands.

Further south the land is “lighter” consisting mostly of sandy or gravely loom which can grow most crops – barley, oats and potatoes.

The rotation generally used of crops was – oats, followed by a root crop potato or turnips or mangolds followed by a grain crop such as oats and sown at he time was hayseed to bring back the grass pasture again.

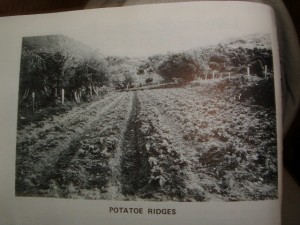

At the very foothills of course and up the mountainside to a height of 100 feet work was much more laborious and far less tilling was done. The main crop was potato, which was true of the entire parish and the variety sown was the Champion potatoes – a grand type.

“Like balls of flour” as one person put it. Most of the work there had to be done by hand, the bawn – ground made into ridges with the spade and then packed with an implement called a “grafan” and then the potato seed or sciolláns as they were called were “stuck”.

The ridges were then covered with farmyard manure and

finally the manure covered with earth dug in the furrows. When the stalks appeared fresh earth had to be put up to them it was called “earthing” the potatoes.

The potatoes when ripe were dug out and put in pits in the field covered with straw or withered ferns and with an outside cover of earth or clay. Those pits withstood the hardest weather, frost or snow. Those potatoes were used by the household little by little as required.

Rich and poor small farmer and big farmer used the method of potato growing all over the parish. Things grew easier somewhat with the introduction of the steel plough.

About 1880 Myles Sweeney’s grandfather invented a timber plough with an iron “sock” drawn by one mule and was the fore – runner of the modern steel plough.

The superfluous potatoes were packed in bags and taken to he market to be sold. Tuogh was famous for it’s fine quality potatoes.

Digging the potato was a very important operation. The farmer generally hired some men for the week; each arrived about 8.00am about mid October. The diggers started together at one end of the “drills” each digger taking two drills, at the time and picking the potatoes in a row.

Each digger dug about 150 to 200 spades – a spade measuring five and a half feet.

The digger did not pick the potatoes, that work was left mostly to the women or very young men, young teenagers. The big potatoes were picked first into “cliabhs”. A “cliabh” as a fairly big bucket made of strong osiers with a capacity of about three stone. As each cliabh was filled one of the diggers took it to the “pit” and emptied it.

The small potatoes the “criocháns” were then picked and put into a separate pit to be used to feed animals especially pigs. Ferns “raitheanach” and considered better covering for the potatoes than straw as they would not rot too quickly and also gave a good ruddy colour to the potatoes.

Oats too had to be sown by the hand – and every farmer was skilled in spreading the seed evenly over the upturned soil. It had then to be covered either by pulling a heavy bush or a homemade timber harrow over the ground.

At the harvest time the oats had to be reaped first in very early days with the reaping hook and then with the scythe. The mower cut a “blow” and then the “taker” made it into sheaves, which in turn were bound by some stalks of oats by the ‘binders’ generally, women.

It was then put into stooks nine or ten sheaves upside down on top of each stook and tied so that they would protect the grain from the rain. The stooks were left in the fields until the grain was well seasoned when it was drawn home and made into a stack – stacking was a very skilled job.

Then came the threshing, separating the grain from the straw. In the early days the threshing had to done with a ‘frail’ two sticks joined at one end with a ‘gad’ a tough piece of honeysuckle stem.

One part was used as a handle and the other was a sort of whip. The threshing was usually done at night in the barn where there was one, or in the kitchen floor of the house. The sheaves were laid flat on the floor and beaten well until all the grain came off.

The straw was removed and another layer of sheaves laid on. The work continued until late in the night and the workman’s wage was calculated on the amount of candles, which were burnt while he worked.

In later years about 1900 came the horse thresher. It consisted of a sort of drum with huge cogs in it and with two strong shafts of wood sticking out from each side – making a sort of diameter. Two horses were tackled to each shaft as they went around and round they put the beaters working connected by a strong bar to the drum. The corn was ‘fed’ sheaf by sheaf into the beaters, which separated the grain from the ‘chaff’.

The straw was made into a Rick and the grain was stored carefully into ‘sop’ or ‘sigeog’ which was made by folding thick ropes of straw one on top of the other – somewhat like a beehive. The horsepower was succeeded by an oil engine, which did the same work as the horsepower.

Next came the ‘Finish’ which simply took away the chaff as well as the straw from the grain. Finally came the Combine Harvester which did away with much of the labour but let took away all the excitement and the joking and laughter of the old days.

A big “meitheal” of neighbouring men had to come to the assistance of their neighbours, which showed the great community spirit of the Irish countryside.

The other opportunity where the community spirit was shown was when once again a “meitheal” had to come together to help the neighbours at the turf or peat cutting operation.

The grain of oats was used during the year to feed the horses and when crushed in the mill was a very healthy food for cows, pigs and fowl, hens, ducks, geese and turkeys.

The straw was used for bedding for cows and sometimes when it was short supply furze or “Ailteann gaolach” was used beneath the straw. It had to be cut with a grubber or in Irish a “gafan”.

Very few other crops were grown except some cabbage, turnip for human and animal food and mangolds for animals.

Another example of friendly relationship between neighbours was the idea of ‘coring’ horses. Many farmers could afford to keep only one horse when two were needed such as for ploughing, he got the loan of a neighbour’s horse and he in turn returned the compliment. A peculiar custom in relation to ‘coring’ was that the person who lent the horse had to convey it in the morning and return for it in the evening.

SAVING THE HAY

This was another big operation. It was cut either by scythe or later by machine. It was then turned by hand with pikes and if the weather was bad, had to be made into small cocks called ‘grass cocks’. As the weather improved it was made in ‘Pike cocks’ and lastly into big field cocks called ‘Wynds’.

The wynds carefully tied with ropes made of hay called ‘Mearogs’. In due time it was taken into the haggard and made into ricks, a portion of the hay was cut off with a hay knife each day to place it in each stall for each cow, as each cow had it’s own special stall where it was tied at night and further more each cow had her own special name – Cooby, Daisy, Polly, Baricky etc.

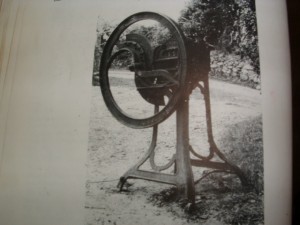

Old Furz Machine

People along the mountainside often found it hard to grow sufficient hay and so they bought it at auctions in farms “over Laune” principally Makey’s and Hassetts. The hay was sold in ‘lots’ growing and they had to cut it and then save it. It was bought by the Irish acre and it was marvellous how accurate they were in measuring the ‘lots’ by just pacing it.

The hay was cut with scythes and you may be sure they shaved the ground as clean as a chin. It was a sight to see two or three mowers one after the other swinging their scythes with the rhythm of rowers in a regatta. The corainin was used if a scythe had a bad edge. The hay when saved was put into wynds.

Then the ‘surveyor’ measured the area and the owner had to pay for it before it could be drawn home. It had to filled into horse carts and how expert those men were at filling a load high up layer after layer and then tied with a car rope.

It was a usual sight in late October to see five or six such carts of hay drawn up in a line in front of a public house in Beaufort, each driver quenching his thirst after a hard day. Each load of hay was a work of art in itself.

Small patches of wheat were grown not for food, but the straw was considered best for thatching houses most of which were thus roofed. The wheat was not threshed in the ordinary way but each sheaf was beaten against a large stone so as to get the grain removed without breaking the straw and so very suitable for thatching. This process was called “Scotching Wheat”.

Most farmers kept a few sheep generally the Border Leicester breed which grew a fine type of wool easy for carding and spinning it into a thread, sometimes there was a black sheep in the flock which was very available as it’s wool needed no dying. Farmers along the foothills of the mountains also were able to keep large flocks of hardy

Black – faced sheep, which thrived not only on the highest mountainsides, but even, grazed on the very summits of our highest mountains.

The land was kept on a sort of commonage with each farmer allowed a certain amount of sheep, and it is known that some farmers have at least 1000 sheep or more each.

In the past wool was valuable but in recent years has declined in value. It is remarkable how each farmer would know his own sheep because to the amateur all sheep look so much alike as it is impossible to know one from the other.

Aiteann Franncach (French Furze) not he common variety growing wild on our mountainsides, but a type set on top of an earth fence to make it higher and which produced long thin soft stems was a wonderful food for a horse.

The soft tops of the plants were cut and brought into the haggard where it was cut up into minute pieces and then when mixed with a little oars, put a real

‘Shine on a horse’s coat’ after a few weeks.

The machine used for chopping was called a furze machine or cabbage machine and if carelessly worked was most dangerous to a person finger.

The Valley of the Laune has been famous for it’s fertility and many agricultural instructors have even remarked as such. It seems that a certain type of mineral called marl, which is a carbonate of lime, is found in the soil. Many holes dug in the area show where marl was dug out to be used as top dress.

The good soil had a twofold result. It produced good crops but on he other hand it raised the valuation of the land, often over a pound per acre, as the land was suitable for wheat – growing which needed the best land.

Lime was much used a few kilns in every townland. Farmers drew the limestone from Killorglin or Firies and burned it themselves – turf was plentiful.

Some farmers along the Laune namely John Clifford and Michael McGillycuddy availed of the First Land Purchase Act – The Ashbourne Act of 1885 and were also far seeing enough to retain both fishing and sporting rights, which many did not and regret it now. Denis Crowley’s, Pat Doyle’s and Gerald Foley’s farms were also bought at the time.

Every small community was almost completely self sufficient they produced almost all their own food – potatoes, cabbage, turnips and vegetables. Meat, bacon and sometimes beef and mutton and fowl, chicken or goose and if you lived near the Black Valley a bit of venison and of course their own Home made bread.

They had their butter and milk. They made their clothes, the weaver made the cloth and the tailor made the clothes, the housewife spun the thread and knitted the socks. They had local builders furniture makers and even shoemakers.

If we take the Green Road (Coolmagort) for example –

Dan Larkin the Weaver lived near the Lios.

Three Tailors, Dan Doyle, Jerh Foley, and John Foley.

Tom Johnson Joiner and Carpenter.

Maurice Foley Blacksmith.

Pats Sheehan, Caroreagh Shoemaker.

Johnny Falvey, Builder.

Con Sullivan, Butcher.

Con Moriarty, a first class thatcher lived not very far away in Dunloe, and in Dunloe also people got their corn around.

All lived within a few hundred yards of each other. The same could be said of many other villages in the parish.

They also had their own fuel chiefly turf. We had two huge bogs in the parish, one the Chapel bog and the other at Kilgobnet with several smaller ones at Ardraw, at Gortbee, at Mealis, and at Dunloe, but unfortunately all those bogs are nearly cut away so that in later years people had to go far away as Glencuttane and Cool to get supplies and draw it home in horse carts and rails.

But during the past ten or twenty years a huge change has come over the methods or agriculture. The first change came with the introduction of Creameries, Beaufort Creamery was opened in 1936 and Kilgobnet in 1959. Gone then were the dairies where the milk was stored in large pans until the cream was ready to be skimmed off and made into butter.

The butter making or ‘churning’ as it was called was a big and hard operation once a week, whether with the staff churn or the barrel churn “ag deanamh cuigine“, and collected the butter with the butter spades. But this work had it’s own compensations, fine fresh butter for the family and then a lovely healthy drink of blathach or buttermilk.

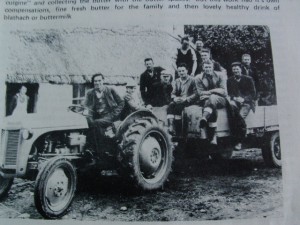

Shortly after the introduction of the creameries came the disapperance of the horse in farm work and the introduction of the tractor as the be – all and end – all of power in the farm. sometimes farms were too small to afford a tractor and so hired men with tractors to do the work. By the way John Clifford, Ards was the first man i saw ploughing with a tractor outside his own farm in the year 1941. He did it in my land here in beaufort and caused a good deal of curiosity and criticism, nothing would grow after such ploughing etc. he used what was called a “drag” plough not attached to the tractor as now but pulled after it.

Every operation has to be done by tractor mowing hay and baling it drawing loads into the barn etc. to suit the tractor fields had to be made bigger and hence the disappearance of fences and in some cases a whole farm was made up of one large plain. gone were the old familiar names of each field – the kiln field, the fort field, the cluan, pairc na carriage, the tuairin, pairc na pluaise, an phairc ard, the long field,etc etc,. Everyone of the householders knew the names of those fields perfectly as did they know the names of the cows, and as the motor car has become the main means of transport, so that country people once famous for their knowledge of local place names and local flora has now become more ignorant of such things than the city or town dwellers, not a good tendancy as knowledge of a place leads to love of that place.